The High Sierras of California

There is nowhere more serene than atop the mighty High Sierra.

Scroll ↓

From The Kern Valley to the Top of Mount Whitney

The High Sierra Trail takes you from Sequoia National Park to the highest peak in the lower forty-eight, Mount Whitney. I walked all seventy-seven miles in six days. Along the way, I was greeted by great granite amphitheaters, rushing rivers, and unworldly views. Let my pictures tell you a story for each day.

Day 1: Cresent Meadows to Bearpaw Meadows

At the trailhead, the wooden sign read “High Sierra Trail 60 miles.” I later discovered that the true length is nearly 77 miles. I started out amongst the last of the great trees and made my way to the edge of the mountainside. The next half of my day would be making my way along the face of the southern slopes of the Middle Fork Kaweah River valley. The views were as oppressively beautiful as the heat rising from the dirt trail underfoot. The trail would become exposed with stands of manzanita, the Sierra’s favorite brush, and transition to Jeffrey pines and the obnoxious White fir with their dead forest floors and witch-finger branches. All White Fir is good for is kindle for devastating life more important than itself.

When I reached Buck Creek Gorge, I could not help but jump in the chilled water. The rest of the day was spent under the trees on the way into Bearpaw meadow. The view from the camp was that of a spectacular sunset against tomorrow’s climb into the granite.

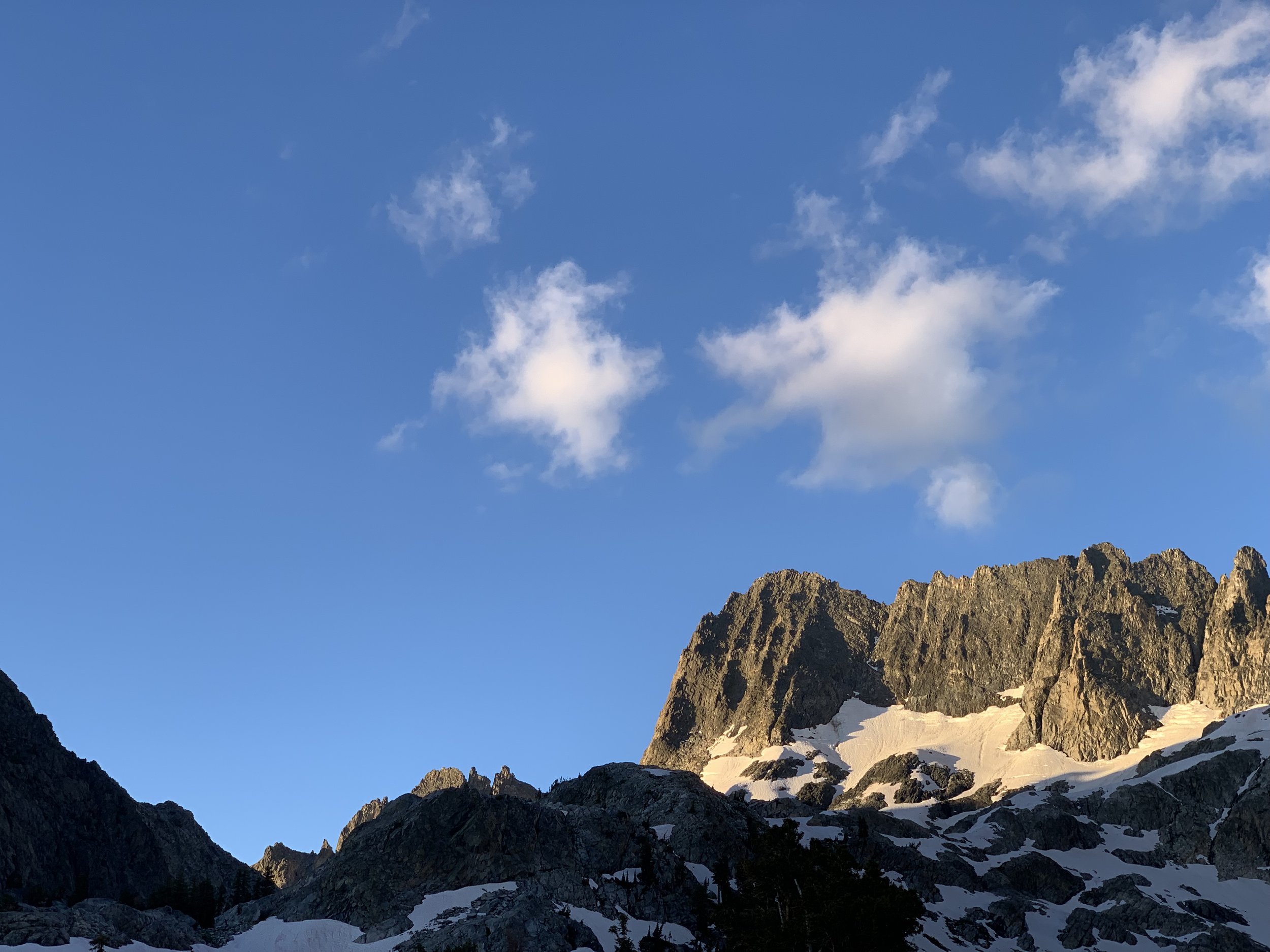

Day 2: Bearpaw Meadow to Big Arroyo

After leaving Bearpaw Meadow, the Sierra granite became the main fixture. The morning haze filled the valley below and glistened like blaring fire above, searing the granite blinding white and leaving dark blue holes of shadows from the cloaking pillars surrounding the valley. I edged around Red Firs and Sierra Junipers. Then, I saw the golden light casting on a waterfall ahead. I walked through the water above and watched as the crystal water sprayed out into the light and became molten steel in its coloration.

I reached Hamilton Lake. I kicked off my shoes and socks and submerged them in the cold water. I watched through the glass water as fish swam gently, spun around, and sped off, leaving a sediment cloud behind. There was a summer hum in the air and in the lodgepole pines, and yet, still unimaginably silent. A thinning waterfall fell on the opposite side of the lake, fed by Precipice above; it was the only true sound to be heard. A small rockfall echoed dully somewhere in the distance.

I looked at where the trail rose two-thousand feet up to Precipice. It was an intimidating view to behold. When I reached Precipice their was still snow in the shadows on the far side of the lake. The water was crystal clear for the first fifteen feet but then turned a sort of blue which hinted at the frigidness of the water. Past Precipice, the land felt good-natured, with small alpine ponds surrounded by small blades of grass. There was only the occasional dwarfed whitebark pine growing between slabs of granite. The rest of the surroundings were mounds of granite the size of small homes and castles yet still towering over such a high place as from where I stood.

The greatest excitement was ahead in the form of the Kaweah Gap. This glacial valley felt more unique than the others I had seen. Kaweah felt incredibly young. The smooth granite and the foliage seemed only to be the spawn of a few generations. The life here felt adolescent, and because of that, the valley seemed to envelope the observer. A quasi-hallucination occurred as I stood at the top of the gap. It was as if the valley was moving like a wave on either side, cresting at the extremes and curling into a perfect funnel of earth. I worked my way down the gap to my serene camp at Big Arroyo.

Day 3: Big Arroyo to Kern River Hot Springs

First thing in the morning, I climbed out of the Kaweah Gap. I watched the eastern sun warm the western High Sierras to my right. Each grove of forest was filled with a few dozen meadows separated by unimaginably large slabs of granite. Whatever ferocity happened beneath the plates to produce such a batholith of granite cannot be imagined. Islands of forests shelved by the white upbringing.

Near the top of the morning climb, I reached the Foxtail Pines, a rare endemic conifer to California that can hybridize with the oldest trees in the world, the Great Bristlecone pine. Separated by a single mountain range, the foxtail may once have been a cousin of the ancient Bristlecone. Not to be outdone, the Foxtail’s bark is a stunning orange with needles older than your grandparents.

The Kern River Valley is a valley as wonderous as the Yosemite Valley. With its intense elevation change, massive granite facades, and even the familiar gentle river cutting the valley in half, there was no less beauty in the Kern. The Sierra’s mechanisms to protect its climate give the individual a sense of creation. Like a clockmaker, the Sierra finds purpose for every imaginable condition. An Afternoon thunderstorm began to develop, the sky greyed, and the air became full of distant booming, but the rain never came, and the lightning never danced around the surrounding mountains. A small wooden sign, no taller than my knee, read, “Kern Hot Springs.” An arrow carved and painted black pointed at a little L-shaped fence. Next to the fence was a small bath and an old rusty black pot.

Day 4: Out of the Kern Valley and into the High Sierra

On day four, we walked the length of the Kern Valley to the headwaters of the Kern River. Our forest disappeared after the third mile. We were still in the valley, and the morning was still in its infancy, but now the land became sparse from an old fire. The ol’ fire gave the valley a new face. The granite that surrounds us in the glacial gutter rests around us like tombstones. Some boulders, bleached white like pure granite, were fifty feet tall and even fatter across the floor. Manzanita, other shrubs, vibrant blues and yellows of budding flowers, and the pesty White Fir began springing from the ash-riddled soil. The land was overgrown at the hip and forever dead above. Only a few Ponderosas were resilient enough. Their bark was black eighty feet into their canopy, and their young were reduced to grey skeletons.

The earth was hotter now and drier. The conifers were now to be dreams of old. Their destruction was final by demons unseen. This land will be lost to low-lying shrubs and hardier, drought-tolerant oaks that will usher in the final and complete extinction of the quilted dark forests that this valley had championed for many a millennium. Not even the granite was safe. As the fire raged, paving its blighted fury across the valley, it penetrated, flirted within, and expanded the stone until pop! The granite split by heat, by destruction, by a process typically embraced but now disguised as an abetting partner.

The standing dead ruminates in my soul. Hundreds of century-old giants now stand like the blackened index fingers of witches. The blue within blue sky contrasts their shadowless blackened bark. The pheromones of these giants, normally an aroma of vanilla emanating from the ambered sap, now from the perspective of a tree, the smell of a corpse, and the visual from a conifer's perspective, a skeleton to a cross. What little force could end my own if such a force could eviscerate such a sturdy and nearly impenetrable way of life?

The trail was granite reduced to sand. It was like stepping over crushed white seashells. The valley walls were beginning to slope out instead of being completely vertical. Trees braved small outcroppings where bright green manzanita bushes padded their understory.

The water evaporated off our clothes in record time. When we left the forest, we were met with the sun-baked western-facing slope of the valley. The mighty Kern was now only a trickling, made up of a multitude of small streams. Ahead, the switchbacks wavered in the heat of the day. I could feel the once wet clothes against my body now drying to a starched and wrinkled cloth against the powdered salt on the surface of my skin.

The Kern valley was becoming a distant sight. The trail was a cliffside that followed a deep canyon down to the valley below. House-sized granite boulders were perched precariously above one another. A small tremor would cause the mighty boulders to roll until they hit the river below.

The sun beat through our clothes, and I felt the sweat on my brow. Through the shimmering heat, nothing could be seen coming up the mountain. We walked on.

The sky above was turning a cobalt blue like it had been above Precipice lake. We were climbing higher now, and the violent canyon to our right was smoothing into a charming creek. The water was a cold white rapid, moving rapidly between the rocks. Our spirits were at an all-time low, but something caught my eye. Oh! The lovely Lodgepole pine! A conifer which any hiker should relate pure bliss with. The trees' tiny purple cones riddle the high forest floor, the bark like a tan crocodile’s scales, and a canopy that can be neatly conical or krumholz by the wind and the snow. When you see these pines, you are amongst the greatest nature there is. Where there is a Lodgepole, there is a waterfall, alpine lake or river, sky-scraping summits, snow drifts, godly meadows full of flowers, and an air thin enough to make you high on it all. The Lodgepoles led us to our camp at Junction Meadow.

Day 5 & 6: Crabtree Meadow and Mount Whitney

The distant mountains did not seem as tall now. I sensed we were reaching the height of the Sierras. There were no great canyons and steep slopes anymore, at least not in the immediate. Where the land pooled into a flat basin, green grass made the meadow. The wind came through the grass, revealing its lighter blue underside and then its shimmering green side. The grass was brown at the center of these meadows where there was a pond not too long ago. Where the meadows ended, there was the treeline. A treeline thinned like the crown of a balding man. The pines grew in straight stands and were separated by granite or meadow.

The trees were beginning to shrink into shorter and more warped shapes. The Lodgepoles, now dwarfed, were coming in the form of krummholz. The land was becoming more and more like a moonscape. A few bunches of whitebark pine, no taller than my knees, were still stretching back toward the sky after months of being under snow.

We had reached the alpine zone. The only green now was the short grass around the small lakes. The terrain looked as if we were walking over the knuckles of a granite giant and, after another small rise, up and over the giant’s arm.

Now, all that was left was the sky and the earth. The sun was warming the beige landscape into a charming amber with shadows from the jagged crags. The sky was a deep blue but for the wonderful array of clouds, perfectly distant from one another like a painting. Nearest to us, there was altocumulus gathering above chilled summits, and then, much closer to the stratosphere, were the cirrostratus and the wistful cirrus curls.

I put my hand on the last boulder overlooking Guitar Lake. The lake was deep blue, and there was a patch of green like a neighborhood lawn. Then, the grass browned and shriveled until you could not make out the beginning of scree or the end of the grass.

Wake up was at three AM on the morning of summit day. It was cold, but the cold night had just started. The land was still. There was no wind, not a snore, nor a stirring, just silence. I could smell the chill coming off the granite but saw nothing.

The path forward was something like Mordor. In the darkness, we carefully stepped over granite slabs like staircases. Our lights were our beacons; there was nothing else. We began to ascend the backside of Whitney. The air was thinning with each switchback. Inches from our feet, the land escaped into vacant space.

And here I was! The gates of Whitney became visible at first light. Her spires and her arthritic fingers breached the underworld. A god or a goddess? Feeling the virgin light and the wind of the new world brushing their fingertips clean. At Trail Junction, we merged left, leaving our backpacks behind, and traveled over Whitney's spine. Guitar Lake below us is like the view from an airplane—the High Sierra’s shadow casting over everything. Then, the final push! Up a scree-covered hump, until at last, the summit of Whitney. The most incredible view in the world.